E46 was the best BMW Three Series ever. One problem: BMW stopped making them in 2006. Even so, how did I end up with a Three that couldn’t be more different from that icon?

Let’s go back a few decades to see if we can find out.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Pathfinder Doorhandle currently lists eleven (11) unfinished and unpublished manuscripts. In the spirit of publish or perish we present the following, blems and omissions included.

True confession time. After six BMWs and ten VWs my heart’s still in the late sixties/early seventies and my rookie driving days with two ‘69 Dodge Dart 340s – a new GTS and a ten year-old Swinger – and a ‘70 Pontiac Firebird Trans Am (Ram Air III 400, 4-speed Hurst). My automotive inspiration back then, first with MOPAR iron and later with the BMW 2002, was the Sports Car Club of America’s Trans Am road racing series that I attended in the late sixties and early seventies at Lime Rock Park in Connecticut and Bryar Motorsport Park (now New Hampshire Motor Speedway) in Loudon. I got to see my boyhood heroes up close and personal while I was a boy: legends like Dan Gurney, Parnelli Jones, Mark Donohue, Swede Savage, George Follmer and less well known contemporary drivers who were nevertheless familiar to me from the pages of Car and Driver, Road & Track and Competition Press & Autoweek.

The big iron originally comprised the Chevrolet Camaro Z/28 and Ford Mustang Boss 302, later joined by the new-for-1970 Dodge Challenger T/A and Plymouth AAR ‘Cuda, street versions of which were powered by the same new, high-performance 340 small block V8 as my Darts, but with tri-power (three 2 barrel carbs) and hokey side pipes, along with suitable go-fast graphics. I drove my ‘69 Dodge Dart 340 GTS Scat Pack to the first Trans Am race I attended at Bryar with my father and my friend Jim McManus.

Watch the fantastic video below, shot in Acton, Massachusetts to get a feel for how cars like this affected sixteen year-old me. I’d have preferred one of these or a Z/28 instead of my beloved 340 GTS but for two facts: I hadn’t yet mastered the manual transmission (those racing homologation specials were stick-shift only) and our “family car” needed a back seat for my chauffeur duties. You see, my parents didn’t drive, so when I came of driving age I got to choose the make and model. Having thoroughly researched the matter – including daily bicycle rides to Commonwealth Dodge in Boston to ogle a gorgeous copper-color Dart GT on the lot, the same car but with a mere 318 V8 – I knew exactly what I wanted when we placed our factory order. The one omission that irritates me to this day is that I forgot to specify the 3:55 rear end instead of the standard 3:23 or the drag race-oriented 3:91, but never mind. I still had the fastest car in the the Saint Sebastian’s parking lot for two weeks until John Welch showed up with his new ‘69 Camaro SS 396 convertible, 4-speed, red with white Z/28 stripes, white top and interior. He’d still have smoked me as he did in the Boston College parking lot even if I’d been running the the drag gears but my Dart was powerful enough to allow me to perfect my drifting skills long before there was a name for such shenanigans. Enjoy:

SCCA’s rules limited the “big cars” to 5.0 liters; the closest Chevy, Ford and Chrysler came to that displacement was 302 cubic inches by combining existing blocks and crankshafts. These cars were purely “homologation” specials, sold to the public in small quantities simply to qualify them for the hotly contested, manufacturer supported road racing series. Thus, their suspensions were adapted to that purpose, so they handled much better than the big block Camaros and Mustangs although they were slower in a straight line, which suited my interests just fine. The races also featured an under two-liter class, dominated by the factory Datsun 510 effort. This brigade also included privateer Alfa Romeo GTVs and BMW 2002s.

Unlike many who cite David E. Davis, Jr.’s famous 1968 Turn Your Hymnals to 2002 Car and Driver article, my early conversion to Bimmerdom began with a copy of Auto Motor und Sport that I bought at Out of Town Ticket in Harvard Square in 1970. Its cover depicted a Colorado Orange and matte black Alpina 2002 lifting its inside front wheel at some exotic European race track and I was hooked, for life so it seems.

My first BMW, a ’71 Colorado Orange 2002, never rolled a single mile in stock form. Instead, it left Foreign Engine Company in Everett, Massachusetts brand new with the following modifications:

Twin Weber 45 DCOE carburetors

Tubular header into an Abarth Exhaust

Koni shocks

Big sway bars

Borrani steel wheels with larger than stock Michelin XAS tires

CD ignition

And best of all, a black, non-dished, 13" MOMO Prototipo steering wheel that followed me to my next Colorado Orange 2002, along with various grille badges, later stolen – an otherwise fairly stock five year-old ‘73.

My reason for the mods was racing, or the closest I could get to it at the time, namely autocross:

When I’d beaten the daylights out of the 2002 for six years I traded it for a year-old 1976 VW Scirocco.

Later, my mother’s hand-me-down 1970 VW Beetle served as transportation when I mostly commuted by streetcar and subway during the week. I even had the engine rebuilt at one point but Boston’s salty winter slush consumed the poor thing and I sold it to my roommate Greg Yahia who completed its death sentence in no time at all by hitting everything but the lottery. Next came my second pumpkin color 2002, then the Trans Am, followed by a rough, twelve year-old ‘68 1600 from California, rust-free but otherwise dilapidated. And that would be my last BMW for the next thirty years.

Fun fact: Pontiac licensed the Trans Am name for use on its OG hot rod and paid a royalty to the SCCA for every Trans Am sold until the final ‘Bird rolled of the assembly line in 2002 as a yellow WS6 convertible.

So, then, why ten VWs over the next three decades? Simple: front wheel drive, essential for my 40 mile commute from Plymouth to Boston and back, five days a week, in the some of worst weather I’ve ever experienced (Bridgestone Blizzaks helped). That and price. To me, the early VeeDubs I owned represented an acceptable, less expensive compromise to feed my German car addiction, built as they were in the Fatherland. All three of my Sciroccos, two of my four Jettas (including my 1980 and the first of my two VR6s) simply had a German car feel that the perfectly nice Mexico- and Brazil-assembled Golf and Jetta(s) simply lacked, including my ‘98 VR6. Of course, all US-spec Volkswagens at the time had German-built engines and transmissions but still…

With a planned move to Florida in 2015, my late fiancé Pamela and I flew to West Palm Beach to buy a stunningly clean 79,000 mile 2002 BMW 325i 5-speed Sport Package for $7,821.00 (with tax and fees) from Autoland of West, a purveyor of fine, gently used sporting vehicles. Over the next eight years I accumulated mostly highway mileage on that lovely car, all the way to 228,829 without major catastrophe. I still regret selling it except that…

…the car was completely gutless, relying on momentum to make time, which it did well – especially on the commute from Inverness to my job at the Mall at Millenia Apple Store in Orlando, routinely cruising 85-90 mph on the Florida Turnpike. And if the sedan was slow, my 2000 323i Touring (which, with typically prescient timing, I bought five days after the first reported death in the US from COVID and sold less than a year later when I lost my job because of the pandemic) was pathetic. Here are the stablemates, both manuals, of course, the wagon being rare in that regard, and both now sadly departed to a good home with my E46 Whisperer.

Searching for a replacement while I drove a work truck, my two requirements were a manual transmission and what my late friend Big Mal called “hosspowahh.” I wanted nothing to do with slow cars and I considered everything from Mustang GTs to SS Camaros… even the huge Dodge Challenger in its various Hemi configurations as a tribute to my original Dart 340s from which it descended. The problem with all of those was that it had been decades since I’d owned a vehicle whose hood I could see from the driver’s seat, including the slope-nose ‘98 F-150. The sheer mass of all three pony cars relative to their interior accommodations was simply an issue I couldn’t dismiss.

So a faster BMW seemed just the ticket.

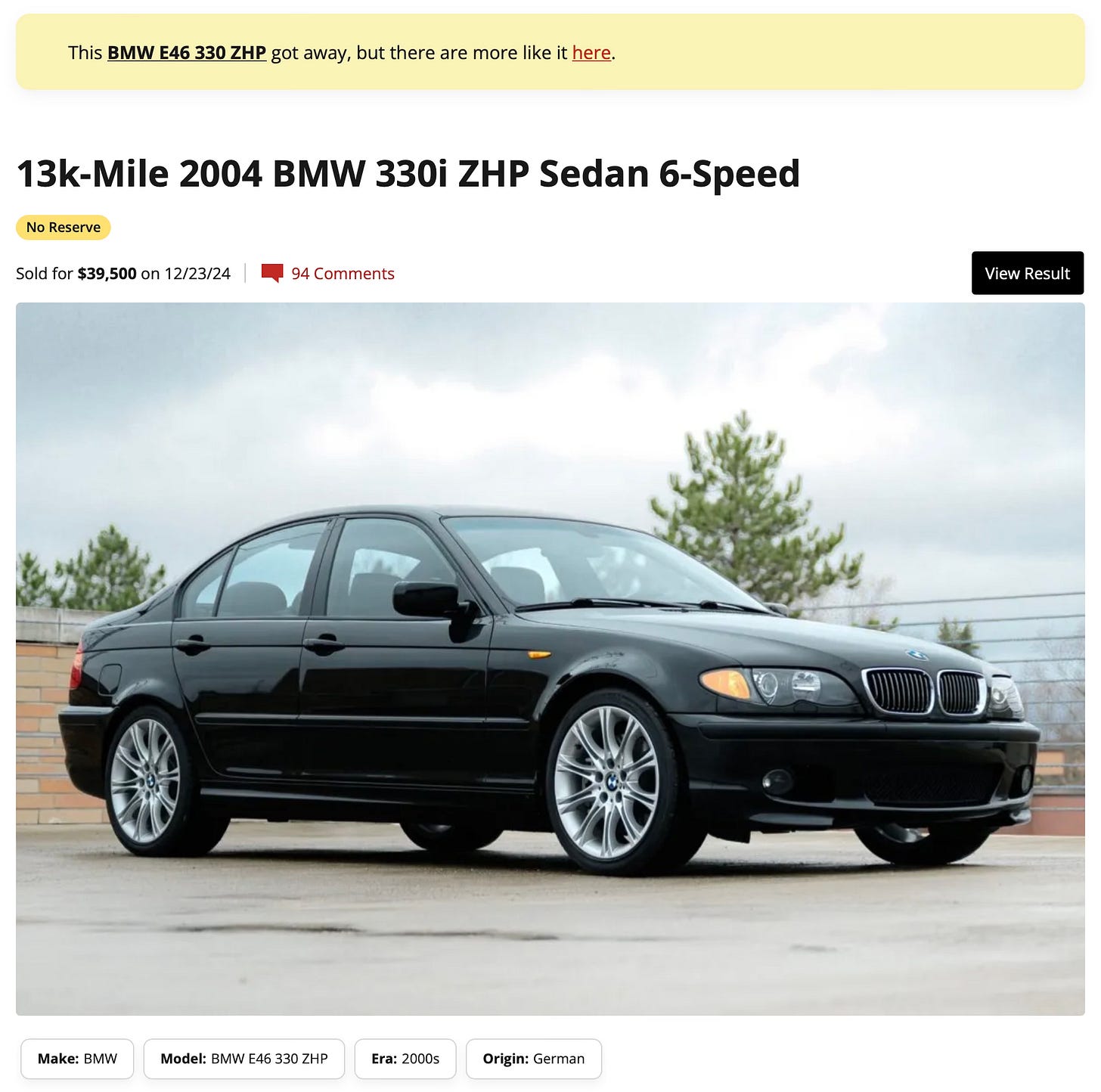

In early 2024 I spotted the ZHP below at a seedy used car dealer down the street and immediately took it for a spin. I’d been looking at E46 330i manual transmission sedans and knew that the rare ZHP performance version was the one to have. It didn’t boast M3 power but unlike that gonzo E46 variant it was available in my preferred four-door body style. It even turns out that M3 owners pay big money to swap “yellow tag” ZHP steering racks into their Ms for its quickness and superior feel, such is the ZHP’s reputation among keen BMW aficionados. Also, the ZHP’s manual transmission has six-speeds instead of five, so naturally that’s what I wanted when I decided to search for my sixth BMW since 1971.

Here’s why that search was doomed from the start – a choice between an OK Imola Red ZHP like the one above that had issues (168,000 miles, automatic, no sunroof, sketchy repaint) for $6,300 or the BaT example below. And what do you do with a twenty year-old, 13,000 mile ZHP you just paid $39,500 for? You certainly can’t daily drive it. Granted, with time and flexibility I could have found a perfect (for me) ZHP.

Instead, I beat mercilessly on my latest Bimmer, a 2014 M335i. Stumbling innocently on that Gray Metallic F30 shows just how dangerous CarGurus and other such apps can be; I caved at sight of its three pedals.

For those interested in details behind the claim made on my latest Facebook cover photo here’s the Machines With Souls article and relevant quote: “The 335i might not have an M badge, but when you skip xDrive and add a six-speed manual, it’s nearly as good as an M3.” Mine is a 335i M-Sport (current G20 naming convention is M340i) with the rare 6-speed manual: only 5.3% of these cars were built with stick shifts, the rest were automatics. I'll devote a future Pathfinder Doorhandle to early ownership impressions of the car as I assume its care and feeding duties.